A Recent FigTree Client Event in Trinidad

For no reason whatsoever, I have decided to take an entirely narcistic approach to this week’s newsletter. I have both asked and answered three investing questions. It’s basically the journalistic equivalent of talking to yourself.

P.S - The probability of you nailing an answer increases dramatically when you make up the questions yourself.

Question 1

This year, the U.S. stock market has repeatedly reached all-time highs, and several financial ratios suggest it may be overvalued. What advice would you have for someone aiming to invest during times of high valuation?

This issue of ‘market timing’ comes up a lot. I get it, nobody wants to deploy their money right before a crash and then wait years before seeing a return on their investment.

Buy low, sell high and all that…

However, the reality is, this market timing obsession is overblown for 2 reasons:

1. Long-lasting market corrections following ‘all-time highs’ are rare.

If you look at all instances where the S&P 500 has been down 10% or more over following each of the 1250+ all-time highs since 1950, for example.

1 year after reaching an all-time high, the S&P has been down 10% or more only 9% of the time.

3 years after reaching an all-time high, the S&P has been down 10% or more only 2% of the time.

5 years after reaching an all-time high, the S&P has never been down 10% or more.

Compared to the frequency of new highs, long-lasting market corrections are extremely rare.

You need to anchor towards to the most probable outcome which is - the stock market moves higher over time. Yes, you may not invest at the exact right time, but the data above shows that it’s unlikely to have a lasting impact on your long-term portfolio.

More often than not, obsessing over the lowest probability outcomes and trying to perfectly time your entry will just leave you waiting on the sidelines for a pullback that never comes.

Take this year for example, in January we were also at all-time highs, and you could easily have made the case that valuations were high relative to historical averages… yet the S&P 500 is up 27% so far this year.

In this case, trying to play it safe by staying in cash while the market was at ‘all-time-highs’ has lost you almost 30%. Meanwhile, everything around you is now more expensive.

In the simplest terms, you need to get exposure to assets that have historically increased in value over the long-term relative to inflation. Sitting in cash is rarely the right option, regardless of where valuations sit.

2. Perfectly timing the market has less of an impact than you would think

Historically speaking, the difference between investing on the worst possible days (the highest point of each year) vs. the best possible days (the lowest point of each year) isn't all that important.

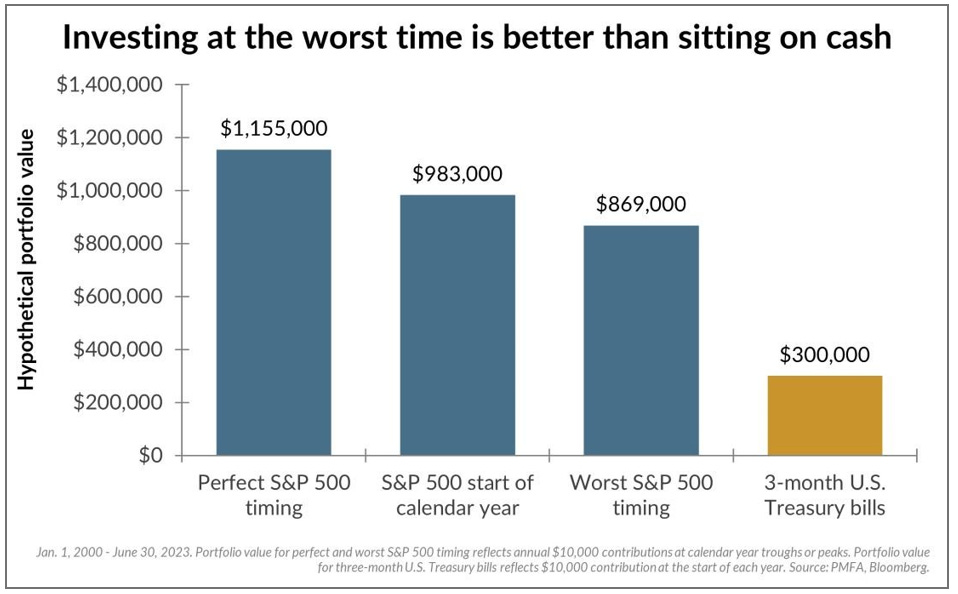

The chart below shows the difference in returns between perfect timing and the worst timing for the S&P between January 2000 and June 2023:

It’s hardly surprising that perfectly timing your investments like some sort of market savant, and investing at the best possible time each year leads to the highest returns, but the difference isn’t that dramatic.

The worst market timer imaginable (buying at the worst possible day each year for 23 consecutive years) would still have done three times better than investing in cash equivalents.

If you are truly having a cognitive block when trying to invest at all time highs, just ‘dollar-cost average’ your way into the market. Invest a little every month or quarter instead of investing your lump sum all at once.

Even if you don’t time it perfectly, you will still be better off over the long run.

Bull case

Pro-business, deregulation, lower taxes/further stimulus? This seemed to be the market’s reaction Wednesday. Small caps and banks were the big winners. The “best ideas” from Wall Street seemed to be Bitcoin, as the administration is expected to embrace vs fight the technology.

Bear case

Bond market continues to sell off, limiting fiscal stimulus and taking stock prices with it. This is the immediate risk in the short term as valuations become overstretched.

Slowing immigration is another drag on growth, but this will take longer to play out.

USD up in the medium term in both situations.

Question 2

Although Berkshire Hathaway itself does not pay a dividend, Warren Buffett appears to have a positive view of dividend-paying stocks, with many of Berkshire's holdings paying dividends. Does a company's dividend record influence your investment decisions?

For Buffett it’s very much a case of ‘do what I say, not what I do’. If you look at the underlying investments within Berkshire, their largest and most successful position in history is not a dividend stock. Apple, which was roughly 40% of their portfolio (before they recently reduced the position), pays out a dividend of just 0.53%.

For me, a dividend is a ‘nice to have’ when I analyze a company but would rarely be a reason I take a position in a stock.

I’m less interested in the income payments that the company pays me each year in the form of dividends and more interested in their ROIC (return on invested capital).

Put simply, I want the company to use my money to generate more and more profits and increase the value of the company instead of paying money back to me directly over time.

If you want income distribution as part of your investment portfolio, then I would suggest doing it through your bond exposure as opposed to heavily weighting towards dividend-paying stocks. Safer government bonds are paying out an average of 4% to 5% in USD terms compared to the 2% dividend yield you get from investing in the Dividend Aristocrats ETF (NOBL), for example.

But hey, that’s just me.

Question 3

Large-cap companies are generally seen as safer investments compared to small caps, but this often means their prices are more efficiently valued. On the other hand, there is a view that small caps, while riskier, can offer more upside potential if the right companies are chosen. What is your perspective on investing in small-cap companies? Would your approach to evaluating small caps differ from your approach with large caps?

I have never been a lover of small-caps if I’m honest.

There is a lot of talk about the potential within the small cap space at the moment and I see the allure. In a market where everything feels expensive, we have a tendency to gravitate towards the asset classes that are uncharacteristically cheap on a relative basis.

Small caps fit nicely into the ‘have underperformed for a long time, and therefore will start to outperform soon’ category.

In theory, small caps should outperform large caps over a long-ish timeframe. After all, they are riskier and should generate better returns over time as a result.

Given this higher level of risk, the sheer level of recent underperformance and the current ‘cheap’ price tag relative to many large-cap names makes for a compelling argument but let’s look at it from the other side.

Why have small caps been underperforming for so long?

You can’t just assume mean reversion. Just because something has underperformed for a long time doesn’t mean it will suddenly experience a miraculous turn around.

You need a catalyst to drive this change in fortunes.

In my opinion, yes small caps are cheap, but they are cheap for a reason.

5 reasons to be exact.

1. Higher Interest Rates

Higher interest rates are an issue for every public company, but more so for smaller ones. Their cost of capital is naturally higher, and the higher-for-longer interest rate narrative will only make this worse.

2. Negative Earnings

The rising number of small-cap companies with negative earnings doesn't help either. In a high-interest rate environment, many companies' runway to success is shortened. More than 40% of the companies in the Russell 2000 (small cap index) don’t actually make any profits- Not ideal in a market that is primarily focused on rewarding stable, cash flow-generating companies.

3. Sector Exposure

It’s easy to look at the sector allocation differences between the Russell 2000 and the S&P 500 and see where recent underperformance may have come from, but there is more to it than that.

Yes, the Russell 2000 has been underweight the best performing sectors (Tech and Communication services). However, the makeup of these sectors is also very different.

For instance, small-cap Tech looks nothing like large-cap Tech. When we talk about the 'Tech Rally,' we are really just referring to a select number of mega-cap names with ludicrous earnings and phenomenal network effects that have seen massive gains in recent years.

If you're a 'pre-earnings' small-cap tech name, you haven't seen a penny of this 'rally.' And I don't see this changing any time soon.

Small-cap financials look nothing like large-cap financials—if you're going to play financials, you want to play the 'too-big-to-fail' names or across the large insurance names. The small-cap financial sector is made up of 60% regional banks and real estate investment trusts. Yes, you get a nice bounce off the lows here, but in my view, this isn't where you want to be over the longer term.

What you're left with is an index that is overweight cyclicals and tilted towards the worst performing parts of their respective sectors. Remember, cheap things can get even cheaper.

4. Structural Issues

This is a less technical take, but it has always frustrated me about any small-cap index.

I don’t want to be in an index where anything that is truly excellent is getting promoted out of the index and into the big leagues (out of Russell 2000 and into Russell 1000, for example).

Every year, your best-performing names graduate. Individual stocks perform SO well, they have to be removed from the index as they have grown too large. And you have to start all over again.

It's Index rotation for all the wrong reasons. I want to hold my winners for as long as possible.

5. Private Markets

The growth in private markets and private market exchanges in recent years has created this quasi- 'Public/Private' market that allows the best-in-class companies to remain private for longer and bypass the public small cap space.

When you have huge flows of capital allowing multi-billion-dollar companies to remain private for longer, the small-cap sector loses out on some of the best performing names that would have historically grown their business within the public market.

I expect this structural trend to persist over time, resulting in many of the ‘would-be’ small-cap gains flowing through private markets instead.

Final Thoughts

Small-caps have historically performed very well at the start of an economic cycle. Once the market has been washed out and interest rates have fallen, the pro-cyclical stance has tended to outperform as the economy picks up. So, if you expect significant rate cuts and a market correction, then small-cap exposure is a trade you should be lining up. I just don’t see it yet.

For me, small-cap exposure has always made more sense as a tactical trade as opposed to a long-term buy-and-hold portfolio position.

Finally, it’s just too nuanced a market to take broad passive exposure. In my opinion, if you are going to play small caps, I suggest focusing on niche concentrated active exposure or, at the very least, taking select sector exposure.

I’m happy to jump in and out of small caps as opportunities present (The recent Trump trade for example), but from a long-term buy-and-hold perspective, it’s just not for me. The opportunity cost is just too high.

But each to their own.

Thanks for reading

At FigTree, we help build, monitor and ensure you execute your financial plan. And as trusted advisor we will be there to help you overcome any stumbling block you encounter along the way.

I’m always happy to help wherever I can so if you want to learn more, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me at [email protected]

Mike 👋